Psychological safety in the workplace is a hot topic, and that’s a good thing. When psychological safety increases, it improves motivation, quality of life, and performance—and who doesn’t want that?

I imagine that psychological safety is something you’ve heard a lot about. And that’s great. It’s very important after all. But what’s less great is that it’s often just the management aspect that gets talked about. Psychological safety in the workplace is really about so much more than that.

Management is only one of five competencies that we need to build psychological safety, and that’s why I’ve written this post. We tend to focus too much on management’s role in psychological safety in the workplace and end up missing the bigger picture. Because of that, we often rely on and expect management and management alone to raise the level of psychological safety. And, in turn, middle managers often expect senior level managers to raise it for them. This is where it falls apart for me, both in my opinion and in what I’ve seen over the years. We can’t always expect other people to raise our safety—some of that responsibility lies on us.

Raising the level of psychological safety in the workplace is the shared responsibility of every single person working at that place.

But what exactly is psychological safety? How do you create it? That’s what I’ll be talking about in this post.

The Origins of Psychological Safety

In 1999, Amy Edmondson looked into why some teams performed better than other teams. At the time, the prevailing views were that team performance either came as a result of people feeling that their work was purposeful and when they had shared values or what it was the result of people’s skills and competency—meaning you either had what it took or you didn’t.

However, what Amy discovered in her research, and what Google later confirmed in their own internal research, was that safe interactions, not just skills and competency, were the key factor to higher performance levels.

Amy’s research has been instrumental to the development of practices that increase psychological safety when people collaborate, and her work has become one of the cornerstones of modern management.

Psychological Safety Defined

Amy defines psychological safety as “a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.”

But in my work with teams, I’ve found that even in teams in which people say that they feel safe to contribute and in which you can observe equal airtime and discussion contribution among team members, some still reported feeling unsafe.

The reason was that the environment made it safe to act (i.e. collaborate) but people didn’t engage socially with people that were different from them e.g. came from different cultural backgrounds, had a different sexual orientation, or were different ethnically, etc outside of their assigned tasks. People didn’t feel safe to be who they were. They felt they were accepted into social circles as long as they adhered to the established norms and interests.

Psychologists have their own definition of psychological safety which can help us understand things a bit better. They define psychological safety as “the ability to show and be one’s true self without fear of negative consequences for self-image, status, or career”. They view psychological safety as a state in which people can be, and are accepted for, who they really are.

There’s a third definition that’s an important piece of the puzzle in getting us to a broader understanding of psychological safety—the neurological view. Neuroleadership,the leadership field of neuroscience, focuses on the brain’s two operating modes. In the first we have access to our prefrontal cortex and thereby also abstract thinking, logic, empathy, language, memory, and learning. In the second mode, known as “amygdala takeover”, we’re in fight, flight, or freeze mode. Neuroleadership defines psychological safety as “a neurological state in which we have access to our prefrontal cortex”.

I view psychological safety as a function of these three definitions combined: feeling safe to act (sta), safe to be (stb), and having access to your prefrontal cortex (pfc). I incorporate all these different views in my own understanding and define psychological safety as follows:

ps=f(sta+stb+pfc)

“Psychological safety is a neurological state that stems from one's own belief that one can be, and will be, accepted for who they are without any punishment or negative consequences such as humiliation or loss of status regardless of whether mistakes have been made. A strong sense of psychological safety in the workplace enables growth, learning, and innovation.

An Integrative Framework for Psychological Safety

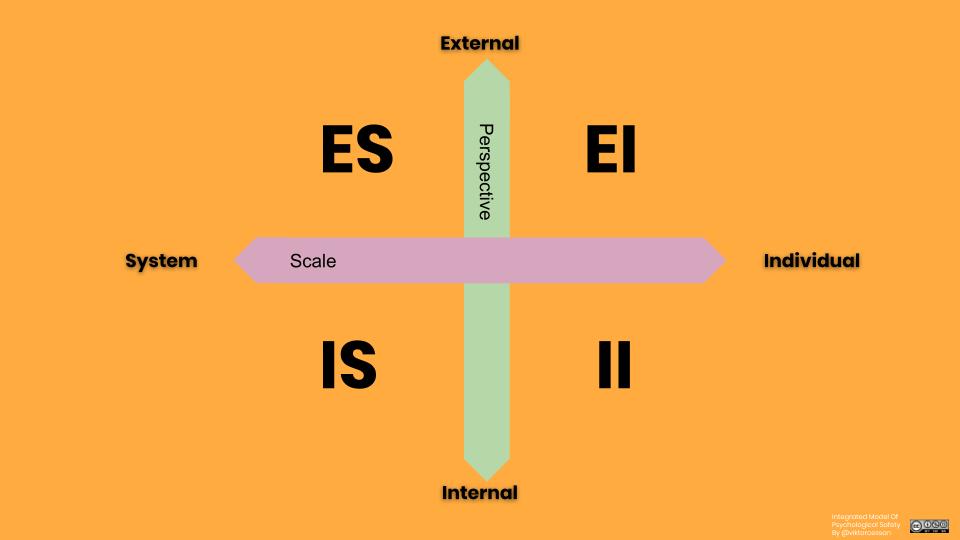

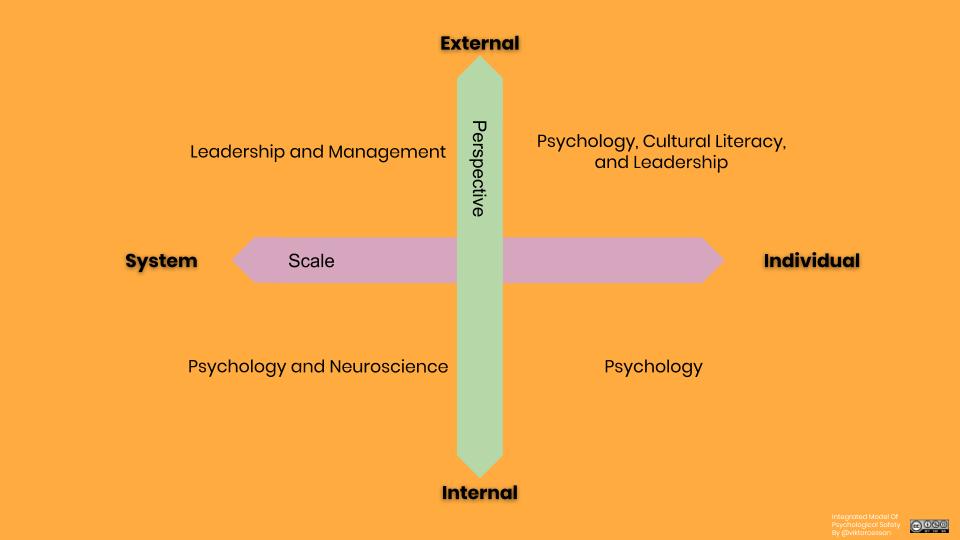

Based on this definition, I’ve created an integrative framework that describes the different parts necessary in order to achieve psychological safety in the workplace.

The framework considers the Scale on which you’re trying to create psychological safety (System or Individual) and the Perspective you’re looking at (External or Internal), i.e. your interactions with other people or those with yourself.

Let’s first take a look at the two axes and then delve further into the four quadrants that I’ve named ES, EI, IS, II.

The Axes of Psychological Safety

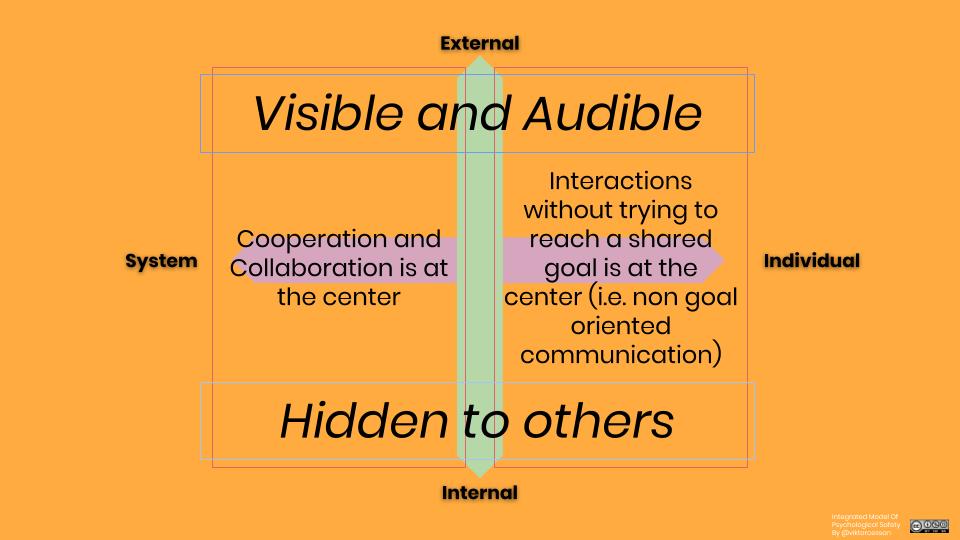

As mentioned, on one axis we have System and Individual Scale. The System side revolves around collaboration while the Individual side revolves around communication and interactions. The difference lies in whether there is a goal or not. For example, if I’m in a meeting discussing our new product launch with a colleague, we’re collaborating. If a colleague and I have a casual conversation at lunch, we’re interacting but not collaborating.

On the other axis, we have the External and Internal Perspective. The External Perspective includes things that happen outside of minds and emotions. These are the things that you can see or hear such as what a manager or team member says or does. The Internal Perspective involves a person’s own thoughts and feelings. These are things that usually can’t be seen or heard directly.

External Systems Quadrant (ES)

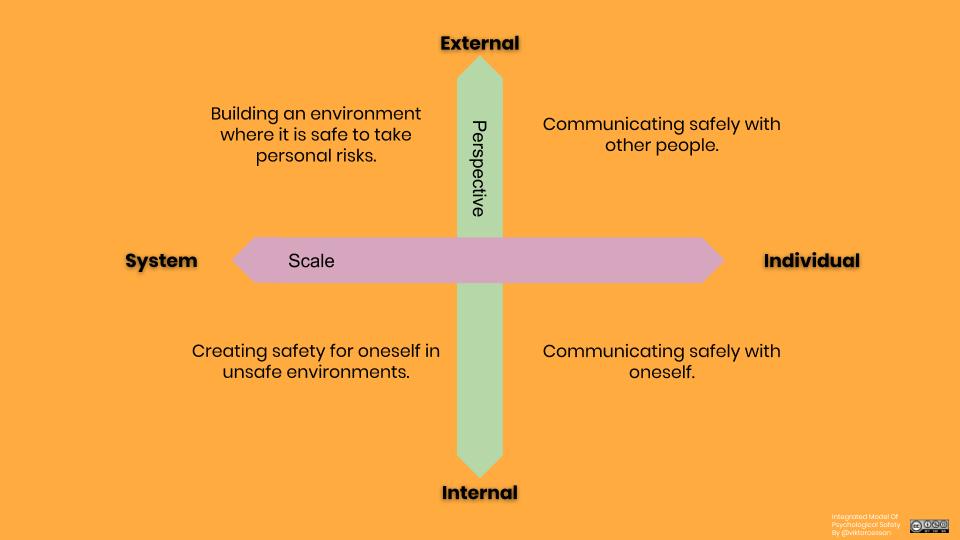

ES is about building an environment with safe interactions. This means that people feel it’s safe to take personal risks such as saying how they really feel, proposing their own ideas, and raising risks and concerns. This is done by removing and reducing negative consequences such as blame, punishment, and humiliation.

Some of the underlying principles are to listen more, encourage curiosity, employ an open mindset, and to make it safe to take risks. But if you’re new to any form of leadership role, that can be quite difficult to translate into constraints to set, structures to build, processes to adopt, exercises to run, or leadership behaviors to employ.

Some examples of how to change the environment and make it easier for people to take risks are:

- Adopt large scale collaboration patterns like SociocracyMake it safer to take risks in one meeting through a predefined format like Bono's 6 Thinking Hats

- Have an airtime budget or a facilitator to help build safe interactions.

There is quite a lot you can try and experiment with, which can be overwhelming for people who are new to psychological safety.

Because there’s so much material on this quadrant, my best tip here is to read up on Amy Edmondson’s work through her books and to study Neuroleadership to understand what our brains respond positively and negatively to. Those two resources together will give you the heuristics and patterns necessary to help you start to create safety-increasing structures.

For those of you interested in more examples of patterns and tools to add to your toolbox, read up on Google’s RE:work, Sociocracy, Heidi Helfand's book Dynamic Re-teaming, Christopher Avery's work e.g. The Responsibility Process, and Liz Weizemen’s book The Multiplier Effect.

External Individuals Quadrant (EI)

I mentioned above that the difference between the Systems and Individual scale is whether or not collaboration is happening with a goal in mind. In the EI quadrant, it’s about experiencing safety in all interactions which are not focused on a goal.

For example, let’s say I enter my office and a colleague says “Hi” and smiles at me. How do I greet this person back? Do I return it or do I just look down? And when I’m chatting with colleagues during a coffee break, am I considering that my topics might be disrespectful to people from other cultures or that they may be considered taboo? Cultural literacy and understanding that people have different needs and values both fit into this quadrant.

Some examples of things you can do to raise the safety in EI interactions are:

- Increase the cultural literacy

- Educate yourself in non-violent communication

- Learn about how the brain is affected by social interactions. I’ve found the SCARF framework (a model that describes social experiences) to be helpful with that, especially if you also reflect on how your behavior and language might affect other people's safety.

Internal Systems Quadrant (IS)

The IS quadrant focuses on managing ourselves at times and in environments and situations that we perceive to be unsafe.

For example, if in the past I have seen that people who challenge management get fired, even when there are valid reasons for speaking up, I might be less inclined to do so. My past experiences could make me more hesitant in the future, even if management specifically asks for it.

Now what can a manager do about this? Perhaps they could try to discuss it with you, but if you’re not willing to engage in such a conversation, you become the one who’s blocking yourself. And that’s exactly it. It’s not always external factors that make the environment feel unsafe to us. Sometimes it’s how we see things and our past experiences that influence our sense of psychological safety.

How can you self-manage that? Well, that’s what Internal Systems is about—self-management in unsafe times.

Some examples of self-management activities you can do to raise the safety in IS are:

- Practice mindfulness, take a walk, vent to a friend

- Create constraints that are necessary for you to feel safe e.g. creating collaboration contracts

- Connect with your feelings

- Choose your self-image a.k.a consciously define how you view yourself

- Express your feelings, needs, fears

- Manage the situation so that it works better for you e.g. by asking for breaks in meetings, asking to move an important meeting to a time when it better works for you etc. Be open to the fact that other people might have different needs and that you might need to find something that works for all of you if you do in fact have conflicting needs.

- Spend extra time preparing e.g. for a presentation or practicing it on a friend. Or, it could be the complete opposite for you, i.e. don’t overly structure a presentation and instead leave room for flexibility so you don’t feel as if you’re reading from a script.

Be aware that learning to do the above things well takes a considerable amount of practice. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) would fall into this quadrant which isn’t something we usually turn to our managers for, and we shouldn’t—that’s the work of trained professional therapists after all.

Internal Individuals Quadrant (II)

Finally, we have the II quadrant. II is about interacting safely with oneself. Things such as self-talk fall under this dimension. For example, speaking aggressively to yourself or being overly critical of yourself creates an unsafe environment internally regardless of what the outer world looks like. One the other hand, being kind to yourself, listening to yourself and your needs without judgment, helps make you feel safer to be as you are.

Consider the difference between these two internal dialogues for example:

“No-one cares about what I have to say, so I shouldn’t say anything”

versus

“This is important to me, so I should say something. Regardless of what other people think, I care about it, and it matters.”

And another example:

“You really need to deliver this on time, people only like you because you’re a high performer”

Versus

“You’ve been going at this for quite some time now, it’s time to take a break. You might be late but that’s just how things will have to be sometimes. People like you for who you are and don’t expect you to consistently overdeliver, and if they do maybe you should find a new place to work.”

All these “I should have” or “I shouldn’t have” type of thoughts fall into this quadrant. Getting rid of self-criticizing thoughts is definitely possible by the way. It requires deliberate practice and energy, but it can be done.

The Integrative Psychological Safety Framework Summarized

Mastering the Quadrants

Because the quadrants of the Integrative Psychological Safety model focus on different things, what you need to improve on differs depending on the quadrant.

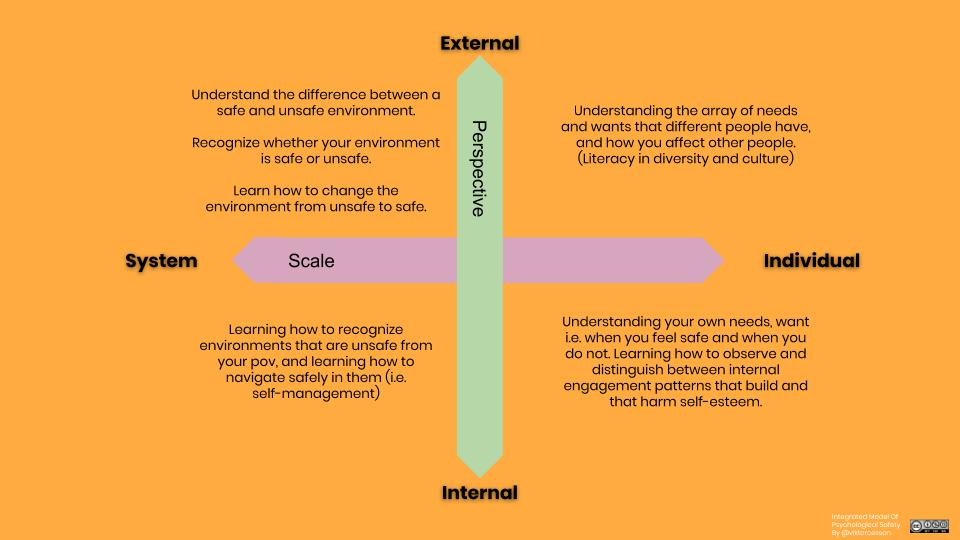

In the ES quadrant, you need to:

- Understand what makes an environment safe and unsafe.

- Learn to recognize whether an environment is safe or unsafe.

- Learn how to shift/turn an unsafe environment into a safe one.

Here are some potential signs that your company has work to do in this area:

- You have unbalanced participation e.g. when solving problems in meetings, one or two people take up most of the talking time or alternatively one or two remain more or less completely silent.

- You appear to have made decisions that shortly after are challenged by people who participated in making those decisions.

- Problems are found late or not at all until failures happen.

- A sizable portion of employees suffer from imposter syndrome.

Learning how to create a more safe environment (ES) requires developing your leadership and management skills. The other quadrants however aren’t about management.

For the EI quadrant you need to:

- Learn to understand the array of needs and wants that different people have.

- Understand how you affect other people. I call this literacy in diversity and culture.

Here are some potential signs that your company has work to do in this area:

- You have a homogenous workplace or teams, low diversity, and/or a monoculture.

- Conflicts are between groups with different norms. For example, you can see this when what’s sometimes called "agile" and "waterfall" mindsets meet, often meaning people who want to collaborate and integrate early vs people who want to hand over completed artifacts to each other. But it could be scientific or political beliefs, etc.

- People are passive aggressive when it comes to addressing issues.

- You have a tech bro culture.

- Learning does not happen and information doesn’t stick—people ask for reminders often and frequently forget.

When it comes to interacting with other people (EI), cultural literacy, psychology, and leadership are the core competencies to develop. I want to specifically mention unbias-training as an important part of this.

For the IS quadrant you need to:

- Learn what environments are unsafe to you and how to recognize them.

- Learn how to navigate safely in such environments (i.e. self-management).

Here are some potential signs that your company, and the individuals, have work to do in this area:

- The company is investing in building a safe environment, but, no matter what efforts management makes, employees interpret malintent.

- People raise concerns in 1:1s that they then do not act on e.g. failing to follow through on offering feedback to peers or management.

If you want to learn more about how to manage yourself to act in an unsafe IS environment, psychology and neuroleadership will be helpful.

Finally, for the II quadrant, what’s necessary is to:

- Understand your own needs and wants i.e. when you feel safe and when you do not.

- Learn how to observe and distinguish between internal engagement patterns that build self-esteem versus those that harm it.

Here are some potential signs that your company and the individuals in it have work to do in this area:

- Individuals suffer from imposter syndrome. (Note that if it happens at scale you have a systemic issue).

- Individuals can’t seem to take a break. This could include overworking themselves, not taking vacation, etc.

- Individuals are unable to forgive themselves for mistakes and move on.

The mind, behaviors, personality, and emotions, are all important aspects to learn about yourself to become an effective leader and collaborator. And overall, II is a lot about psychology.

Interventions that help increase Psychological Safety

Different quadrants call for different interventions of different types. Creating one environment that perfectly caters to everyone’s needs oftentimes might not be possible. There are however still some things that you can do to increase psychological safety in your working environment.

In the workplace, management can have a positive impact on the External perspective. Internal interventions, on the other hand, are mostly up to us to explore.

The following interventions (mostly focused on the External Perspective) have helped me and my organizations immensely over the years. I hope they can be a starting point for improving psychological safety in your workplace as well. These include:

- ES - Be explicit about decision-making models in advance.

- ES - Provide ways for people to disagree, i.e. agree on how you want to disagree.

- ES - Create structures that make divergence the point.

- For example, ask people to note down as many diverging opinions as possible or ask people to only bring their critiquing hats to a specific meeting.

- ES- Adopt structures that cater to different people’s working styles.

- Some people prefer to think in advance about a problem and some prefer to talk while thinking. Send out material for reflection days in advance, ask people to prepare their retrospective notes the day before (by sharing the format), etc. This will give people who want to think on their own first more time to do so.

- ES - Create safety feedback loops.

- You could choose to focus one or more retrospectives on psychological safety specifically, like in the example above. You could also make it a part of a buddy feedback system (if you have that in place) by asking people to share examples of situations in which they’ve felt safe and unsafe working with each other.

- You could have a conversation about airtime and chart out what their individual and collective use of airtime looks like.

- ES - Create structures that balance airtime.

- Some video chat platforms now measure who speaks the most. But you could also ask the facilitator to monitor and visualize it.

- You could allocate a time budget per person and meeting.

- You could agree on a non-invasive interrupt signal to employ when airtime starts getting out of balance.

- ES+EI+II - Encourage self-exploration.

- I personally believe most people can benefit from therapy. So if that option is available to you, going to therapy can be a helpful personal intervention that gives you those tools necessary for IS.

- There are lots of exercises that help people learn about themselves via exploring behavioral styles and personality. But unless you’re trained in this, or even better a trained therapist who can help, this is an area to stay out of. That doesn’t mean there are no exercises to run. My Value Cards exercise is one example of a safe exercise to run, but there are lots of getting-to-know-each-other exercises on mural with free exercise templates and guides to use and follow. You could also try it out by asking:

- What are some things that increase your feeling of safety?

- What are some things that reduce your feeling of safety?

- What are some concrete examples of when you have and have not felt safe in this team?

Putting the Integrative Framework of Psychological Safety into use

For starters, I hope seeing the four quadrants broken down and displayed visually in this way has helped you reflect on where you and your organizations are strong today and where they could use a bit more work to further improve psychological safety in the workplace.

If you’re a manager and working in an organization that’s starting to talk about psychological safety, try using this framework as a common language to understand which quadrants you’re investing into most. Only investing into one will create an imbalance that may appear to improve things in the beginning, but eventually you’ll start seeing low psychological safety that can’t be raised despite efforts. That’s when being able to reflect on all four quadrants will help you understand where the imbalances might lie.

As a team, if you’re exploring this topic, you could read this blog post together and then converse on which areas you as a team see development potential in and where you individually might be struggling the most.

Whatever you do, if you make use of this in any way, please let me know, I’d love to hear what you tried and how it went.

-Viktor

3 Comments

Rejane da Silveira Oliveira Cipriano

Great and precious information Psycological Safety. Everything that I trully Believe.

Gratefull for this.

Rejane – Scania IT

Nozuko Motswiane

Lovely article, I am yearning for an action plan kind of read on how to improve psychological safety in the workplace.

Pingback: